APRA Chair Wayne Byres - Speech to the 2021 UBS Australasia Conference

Thank you for the invitation to be part of this year’s UBS Australasia Conference.

The agenda for this event is wide-ranging and forward-looking, roving well beyond the financial sector that is my domain. The overarching theme of ‘Resilience & Sustainability’, however, is one that aligns well with APRA’s role as a prudential regulator, and is at the heart of much of our work agenda.

When it comes to building financial resilience in the banking sector, we have been pursuing a number of important and inter-related pieces of work which will result in three papers that are being published before year-end. When put together, they lay out the architecture for ensuring bank resilience in Australia, and I want to talk a little about each today.

The first is the bank capital framework. Capital is at the core of any prudential framework, designed to provide a high degree of confidence in the stability of the banking system regardless of where we might be in the economic and financial cycle.

The second is the macroprudential framework. It has taken on a more prominent role in recent years, and is used in response to the cycle. It can be deployed to lean against the wind – whichever way the wind is blowing.

The third is the framework for resolution, including the use of additional loss absorbing capacity (LAC). Resolvability and LAC do not provide support to a bank on a going concern basis, but play an important role if a bank is in difficulty. You can therefore think of it has being able to be deployed if needed at the bottom of the cycle (and perhaps at others times too).

All three frameworks are foundations for safety and stability in the banking system – at whatever point in the cycle we might be at. We published our macroprudential framework paper last week; we will publish the final capital framework before month-end, and we will follow that before year-end with another paper on resolution planning and loss absorbing capacity. Each paper is significant in its own right. But it is important to see the three frameworks as part of an overarching and reinforcing architecture designed to fortify the financial soundness of the Australian banking system throughout the economic cycle.

An unquestionably strong framework for bank capital

Let me start with our capital reforms. Capital is the cornerstone of a bank’s financial resilience, and the regulatory capital framework is the primary tool through which APRA establishes a core level of safety in the system.

The capital framework is designed to be risk sensitive. It will therefore respond to differences in the portfolio composition of banks, and to some degree to the ups and downs of economic and financial activity. But by and large, the capital framework can be thought of as a constant through the cycle, calibrated to achieve a high level of safety and stability so that banks can absorb losses and continue to provide critical functions through good times and bad.

The capital framework has also been, for almost all of the 7½ years I have been the Chair of APRA, a work-in-progress. We have undertaken extensive consultation and analysis to examine how we can improve the capital framework and ensure it best delivers ongoing stability.

There have been two primary objectives of this work:

- First, to implement the Basel III framework that is due to come into effect around the world from the beginning of 2023. As a small-ish but open economy that relies to a large extent on accessing foreign markets, Australia benefits from being seen to adhere, and in many cases clearly exceed, international minimum standards in much that we do – and financial services are no exception.

- Second, to deliver on the 2014 Financial System Inquiry recommendation that APRA set capital standards such that Australian bank capital ratios were ‘unquestionably strong’. Although we believe that current bank capital levels meet that aspiration, the regulatory standards that underpin capital levels in the system need to be strengthened accordingly.

Fulfilling those two objectives is no small task in itself, but we made it tougher by adding another five. In reforming the capital framework, we also sought to:

- enhance its risk sensitivity in key areas, including through applying more capital overall to residential mortgage portfolios given the structural concentration in this asset class for Australian banks;

- improve the flexibility of the framework, by providing a larger proportion of capital to be held in the form of capital buffers that can be drawn upon in times of stress;

- improve transparency and comparability, by increasing the alignment of APRA’s standards with the international Basel framework and making local adjustments easier to discern;

- support competition, primarily by narrowing the gap in capital requirements between the standardised and modelled approaches, and adding in safeguards to ensure the two approaches do not excessively diverge; and

- increase proportionality, through the introduction of simplified capital requirements for smaller, less complex banks.

If hitting two birds with one stone is difficult, hitting seven is a real challenge!

Inevitably, there have been trade-offs: sometimes, for example, calls for more risk sensitivity can be at odds with meeting the internationally agreed Basel standards; the desire for international comparability can be at odds with the domestic goal of ‘unquestionably strong’ capital ratios; calls for more consistency in risk weights to aid competition can be at odds with improving both risk sensitivity and proportionality. Nonetheless, I think we think we have made a good fist of balancing these considerations through extensive consultation, feedback and analysis (albeit that I am sure that no one will be completely happy and everyone will have a particular detail they would prefer was different) and will release the final package of standards in the next couple of weeks.

There will be a great deal of detail to digest when the full suite of standards is published, but in the time I have today I want to highlight a few of the key features of the new framework.

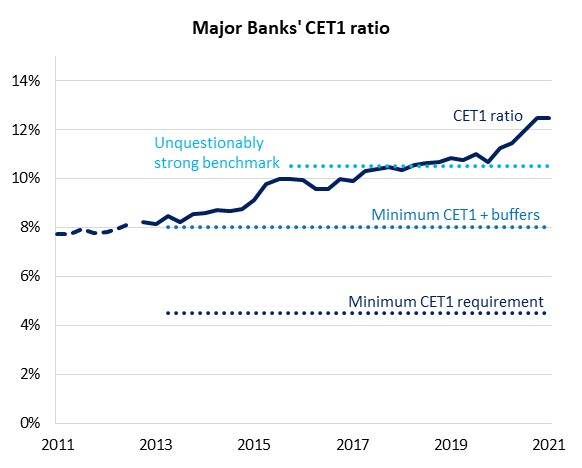

First, we will be raising minimum capital requirements consistent with the benchmarks we set in 2017 when we published our assessment of what ‘unquestionably strong’ standards would entail.1 We have sought to hit these benchmarks across the system as a whole – acknowledging that results for individual banks will inevitably vary either side of the target. But the key message is that minimum regulatory requirements are strengthened under the new regime. For the largest banks, we fully expect they will be in the top quartile of capital strength when measured on a consistent basis against their international peers.

Second, although minimum capital requirements are increasing to achieve our ‘unquestionably strong’ objective, the banking system already has more than enough capital to meet the new requirements. In 2017, when we published the benchmarks for ‘unquestionably strong’ capital ratios, our commitment was that banks with capital ratios above this level could be confident – even though we hadn’t yet designed the new framework – that they would meet whatever new requirements came into effect without the need to raise capital. That will be the outcome. (And, in an international context, that means they will be compliant with the new Basel standards without the need for the extensive phase-in arrangements that will be needed elsewhere.)

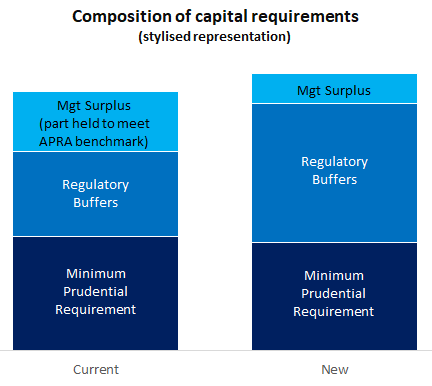

Third, the strengthening of capital requirements will involve a larger share held in the form of regulatory buffers that can be utilised in times of stress. A portion of this buffer will be constant, and another portion – the Countercyclical Capital Buffer, which I will come back to when I talk about the macroprudential framework – will be time-varying. The larger share of minimum capital requirements held in the form of buffers provides more flexibility for banks and regulators to respond in an orderly fashion to periods of stress.

Fourth, because we are rebasing risk weights to make them more aligned with Basel standards, reported capital ratios will be slightly higher than under the current framework. The analogy I have used previously to explain this is it is akin to shifting from imperial to metric measurement – the number of units increased when we changed from inches to centimetres, even though nothing actually got longer or taller. From the introduction of the new framework in 2023, many of the rules of thumb and yardsticks used today – including the 10.5 per cent CET1 benchmark applied to the major banks – will no longer apply. We will have a new framework that provides clear minimum requirements for banks, comprising a minimum CET1 requirement and a series of buffers – above which banks will be able to set their own target operating ranges.

And fifth, the transparency and comparability of the framework will be improved. This will be achieved in two main ways. For those of you interested in international comparability, the differences between the Australian regime and the Basel standards will be lessened in some areas, and many of the local differences will be easier to identify and (if needed) adjust for. This should improve the understanding of the underlying strength of the Australian system. And from a domestic perspective, the requirement for banks using advanced modelling approaches to also report their capital ratio under the standardised methodology will ensure there can be a more meaningful like-for-like comparison between domestic banks.

Overall, we believe we have created a strong and flexible capital framework. It complies with the minimum Basel standards (without the need for a lengthy phase-in). It lifts minimum requirements consistent with our ‘unquestionably strong’ objective. And it is more risk sensitive, flexible, proportionate and transparent than the current framework. Of course, no system is perfect, but we are confident the new framework will provide a strong regulatory foundation for the ongoing health and stability of the banking system – whatever ups and downs might lie ahead.

Macroprudential framework

Those ups and downs bring me to the macroprudential framework.

Macroprudential policy is an important accompaniment to traditional microprudential requirements. It differs, though, in a couple of important dimensions: macroprudential policy measures are typically temporary and counter-cyclical in nature. In particular, they seek to build additional resilience or reduce excessive risk-taking by the financial sector during an upswing in the financial cycle, and can provide flexibility to support risk taking and economic activity in a downturn.

In setting out our macroprudential framework last week, we sought to provide more transparency to the objectives we pursue (and those we don’t), the tools we have available, and the way in which we implement macroprudential policy.

In theory, there are many different macroprudential tools APRA could employ:

- capital-related tools;

- credit-related tools;

- liquidity or market-related tools; and

- structural tools.

In practice, most of the action will take place through capital- and credit-related tools applied to the banking sector, reflecting the critical role that leverage plays in considerations of financial stability.

We have built macroprudential flexibility into the capital framework. This is most obviously through the greater prominence of buffers within the framework, and in particular the setting of a non-zero Countercyclical Capital Buffer as a default level.

The CCyB was introduced into the Basel framework in 2011 to give prudential authorities the ability to take account of swings in the macro-financial environment in which banks operate. According to the Basel standards, it is to be deployed “when excess aggregate credit growth is judged to be associated with a build-up of system-wide risk, to ensure the banking system has a buffer of capital to protect it against future potential losses.”2

APRA has not deployed the CCyB in Australia to date, largely because it risked complicating the build-up of capital that was occurring in response to the ‘unquestionably strong’ benchmarks. However, as we settle into the new system, we see benefit in having a requirement that can be dialled up, and down, in response to the peaks and troughs of the economic cycle. So, we propose to utilise a default setting of 1 per cent for the CCyB, giving us scope to adjust this over time in response to conditions.

Of course, we may not choose to use capital-related measures at all. Given what we have experienced in Australia in recent years, targeted credit-related measures have tended to be the tool of choice. Each of our various interventions in relation to mortgage lending – benchmarks on the growth in investor lending introduced in 2015, limits on the share of interest-only lending implemented in 2017 and, most recently, an increase in the serviceability buffer initiated from the end of last month – have been targeted at specific vulnerabilities that were evident at a particular point in time. Having a wide range of options at our disposal is helpful for ensuring we can address emerging risks in a targeted manner, limiting spillover effects and unintended consequences.

Having the capacity to act counter-cyclically – in both directions – provides important support for ongoing stability. We therefore see the macroprudential framework as providing an important complement to the capital framework. It provides a set of additional tools that can be used – judiciously and sparingly – to head off emerging risks that threaten financial stability, and provide support for the ongoing provision of financial services, at different times of the economic cycle.

Resolution framework and additional loss absorbing capacity

That brings me to the third and final of the papers we will be publishing: our proposed framework for resolution and additional loss absorbing capacity.

There is plenty of evidence from around the world that the disorderly failure of a financial firm can have significant negative economic and social consequences. It can impose significant costs upon, and cause major disruptions to, individuals, businesses, communities and the financial system.

Taxpayers funds all-too-often need to be put at risk. And failure usually occurs just at a point in the economic cycle when it can least be afforded or managed effectively.

No matter how strong the capital framework, or effective the macroprudential framework, it is not possible to guarantee that a financial entity cannot encounter severe stress, potentially threatening its ongoing viability. Micro- and macroprudential policy and supervision can reduce risk, but not eliminate it. It is therefore important that financial firms prepare for stress that may threaten their viability, by developing options to either recover their financial position or exit the industry in an orderly fashion (a ‘financial contingency plan’). But even a firm’s best laid plans may not work, so APRA also needs to have a pre-positioned back-up plan (a ‘resolution plan’) when all else fails.

We have devoted considerable resources in recent years to enhancing contingency planning within the financial sector, and developing our resolution plans. But unlike most other jurisdictions in the world, we have done so without the foundation of a set of formal prudential requirements. Our upcoming paper on APRA’s resolution framework will mark the commencement of formal consultation on such requirements.

In undertaking this work, our goals are threefold:

- that APRA-regulated entities are prepared for stress that may threaten their viability, and understand what options they have to respond;

- that if an entity is reaching the point of non-viability, it can be resolved in an orderly manner such that key customers – depositors, policyholders and fund members – are protected and system stability is preserved; and

- that wherever possible, solutions to financial stress – either contingency planning or resolution – are not reliant on taxpayer support.

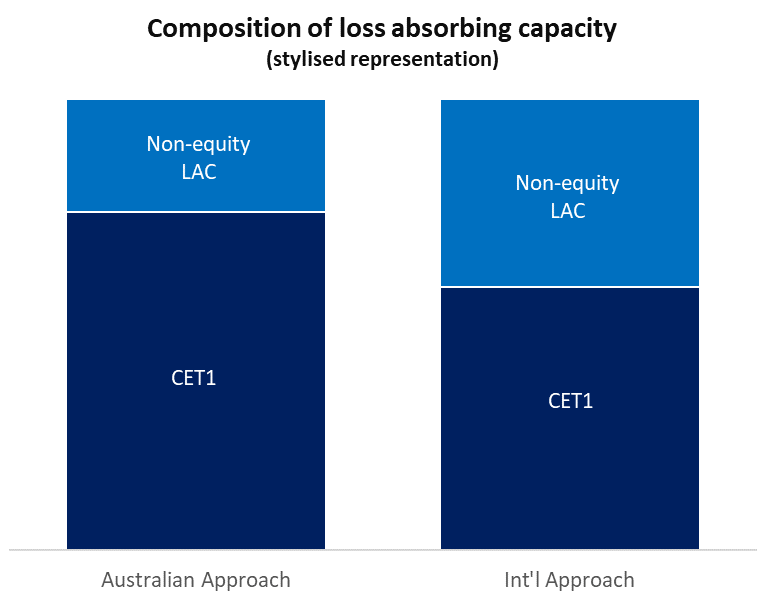

Within this broader framework, we will also be finalising our approach to additional loss absorbing capacity (LAC). In 2019, we established a requirement for the banks we regarded as domestic systemically important banks – the four majors – to maintain additional LAC to support their orderly resolution.

Unlike peers elsewhere, we did not design new instruments to meet this requirement – we utilised the existing regulatory capital structure. Our approach was to require, as a first step, an additional 3 per cent of risk-weighted assets to be held as capital to support resolution. The banks chose to meet this by building up their Tier 2 capital, and despite some initial concerns about market capacity, this has been done in an orderly manner.

At the time, we noted that our ultimate objective – to achieve an overall level of LAC in line with international peers – would probably require additional LAC in the order of 1 to 2 per cent of risk-weighted assets. This would position the majors with an overall level of LAC broadly in line with international peers, albeit with a stronger focus on CET1 capital through the unquestionably strong calibration of the capital framework. We continue to think that remains the right objective.

Concluding remarks

Let me now wrap up.

The architecture I have laid out today is not new. The component parts have been part of APRA’s armoury for many years in different shapes and forms. But what we have been doing over the past couple of years is making sure the individual components are optimised to work together and reinforce one another. We have also sought to make sure the overall framework works for Australia, and in the interests of the Australian community.

The strengthening of the architecture should be seen as a natural evolution – consistent with APRA’s ongoing resilience mandate – rather than signalling a major new policy direction. As I noted, the Australian banking system is already operating with capital levels in excess of that required by the new capital framework. The macroprudential framework does not introduce significant new approaches; it simply seeks to provide more transparency as to how APRA will go about applying macroprudential policies. Our resolution framework will formalise much of what we have been applying through supervision in recent years. So, Australian institutions are well equipped to handle all three. However, that should not be taken to diminish the significance of the three frameworks. As I said at the beginning, each is important in its own right. And taken together, they provide the critical foundations for continuing to deliver Australia a strong and stable financial system throughout the economic and financial cycle.

Footnotes:

1 In simple terms, an ‘unquestionably strong’ calibration would involve minimum capital requirements that were about 50 basis points higher for banks using the standardised approach, and 150 basis points for banks using advanced modelling approaches.

2 Note the emphasis is on protecting banks from the cycle, not the other way around.

The Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) is the prudential regulator of the financial services industry. It oversees banks, mutuals, general insurance and reinsurance companies, life insurance, private health insurers, friendly societies, and most members of the superannuation industry. APRA currently supervises institutions holding around $9 trillion in assets for Australian depositors, policyholders and superannuation fund members.